HISTORICAL BEGINNINGS OF FUR FARMING

Were red foxes farmed on the islands of northern Scotland in the late Iron Age? Photo: Joanne Redwood, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fur clothing goes back to the Stone Age (ended between 4000 and 2000 BC), but for most of prehistory, furs came from the wild. The exception would have been the skins from sheep and goats, which began to be domesticted in about 10000 BC. Herders were farmers, and wore their animals’ fur, but it wasn’t really what we think of as fur farming.

Fast forward to the late Iron Age, when archaeologists say it’s possible that inhabitants of islands off northern Scotland may have been breeding red foxes and other furbearers for their fur. But the evidence is not conclusive, and even if fur farming did occur on islands like Orkney, it didn’t survive the Viking invasion of around 800 AD.

We then have to wait more than a millennium before the advent of what we can call modern fur farming.

The first recorded attempt at farming mink took place during the American Civil War (1861-65), at Cassadaga Lakes in New York, to provide soldiers with warm winter clothing. This was followed in Richmond Hill, Ontario, where the Patterson Brothers built a herd of 130 mink in the 1870s. But it seems this was just a sideline at most, and maybe just a hobby, as their main business was manufacturing farm machinery, and there is no record of them ever selling pelts.

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND

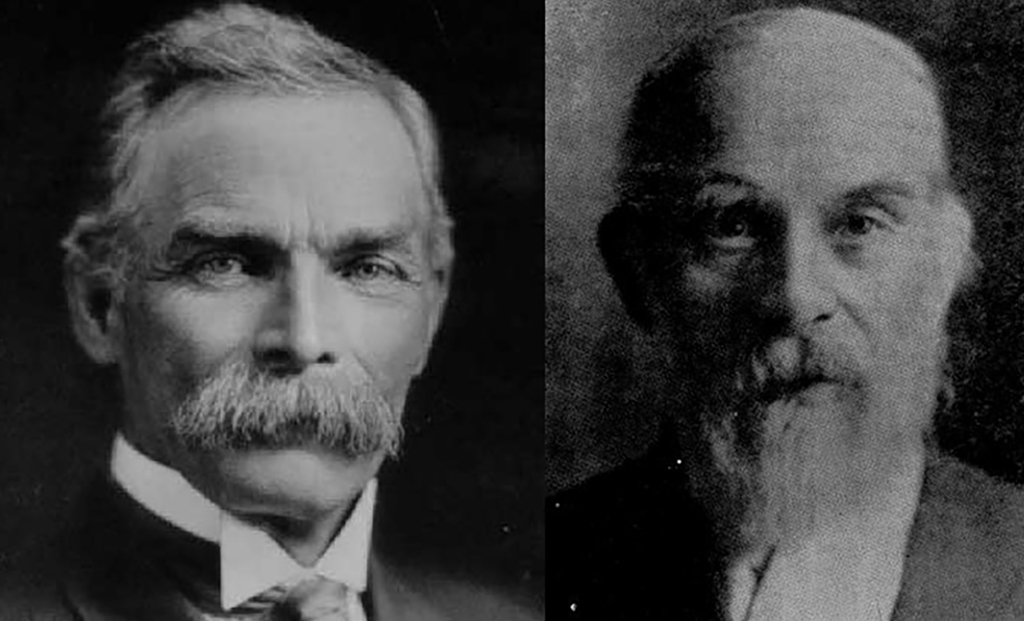

Charles Dalton and Robert Oulton were the founders of modern fox farming.

Historians consider the starting point of modern fur farming as a business to be 1895 on Prince Edward Island, when the breeding of silver foxes became a hugely lucrative venture.

The story began some years before when a Mr. Lamb dug a few young foxes from their den in the woods near what was then the tiny settlement of Tignish. (It still only has just over 700 inhabitants today.) These foxes were “silver-blacks”, a naturally occurring mutation of the Canadian red fox. Lamb then sold them to Benjamin Haywood, who tried briefly to raise the foxes in a shed adjoining his carriage house before turning them over to Charles Dalton.

After some unsuccessful efforts to raise the foxes in cages in his barn, Dalton formed a partnership with his friend and hunting companion Robert Oulton, who had already been experimenting for a few years with breeding foxes. Dalton would handle the finances and marketing, while Oulton would take care of the animals.

Oulton decided to try raising the foxes in a more natural environment, so he fenced in a section of spruce and hardwood forest on his isolated Cherry Island farm (later renamed Oulton’s Island in his honour). By 1895, Oulton’s farm had bred and raised several foxes to maturity in captivity. This was the first time this had ever been achieved, except, possibly, for those efforts in northern Scotland over a thousand years before.

As Oulton and Dalton worked to develop a consistent strain of silver-black foxes, they began selling the pelts of the animals they did not retain for breeding at the January sale of C.M. Lampson & Co., in London, England. They shipped the furs from a small PEI harbour in the dead of night, to keep their production secret, and for good reason: in 1900 they received $1,807 for a single fox pelt, an enormous sum at a time when an average Island farm worker could expect to earn $320 for a year’s work!

As production increased, it became impossible to keep their project secret, and in 1900 Dalton and Oulton expanded their partnership into the “Big Six Combine”, with several neighbours. The group pledged never to sell live animals outside the group, but their monopoly was broken in 1910 when the nephew of one of the partners, Frank F. Tuplin, sold two pairs of live silver foxes for $10,000.

During the fox boom that followed (1910-14), fortunes were made. In 1910 Dalton sold 25 pelts in London for more than $20,000. The commissioner of agriculture reported in 1914 that the 3,130 foxes raised on the Island’s 277 ranches had a value of $14 million – an average of almost $4,500 per pelt!

Dalton set up a new farm near Charlottetown, PEI, to supply the Charles Dalton Silver Black Fox Co. Ltd., a new venture for which he had received $400,000 in cash and $100,000 in shares, in 1912. The fast-growing fox industry was riding so high by then that the train carrying breeding stock from his farm in Tignish was dubbed the “Million-Dollar Train” in the local papers.

With the outbreak of World War One, however, Dalton must have felt that the “soft-gold” rush was peaking; he sold all his fur interests and devoted the rest of his life to politics and philanthropy.

He was elected to the Legislative Assembly in 1912 and 1915, where he served as minister without portfolio. He also donated generously to fund a tuberculosis sanitarium, schools and help for the Island’s poor.

In 1930, at the age of 80, Dalton was appointed lieutenant governor of Prince Edward Island, a position he held until his death in 1933.

Today, there are only a few small fox farms remaining on PEI. But the breeding stock and husbandry techniques developed by Dalton, Oulton and other founding members of PEI’s Big Six Combine were used to launch fox farming operations across North America, Europe and Asia.

With special thanks to Alan Herscovici, whose article, “A personal voyage to the origins of fox farming” provided much of the material for this page.