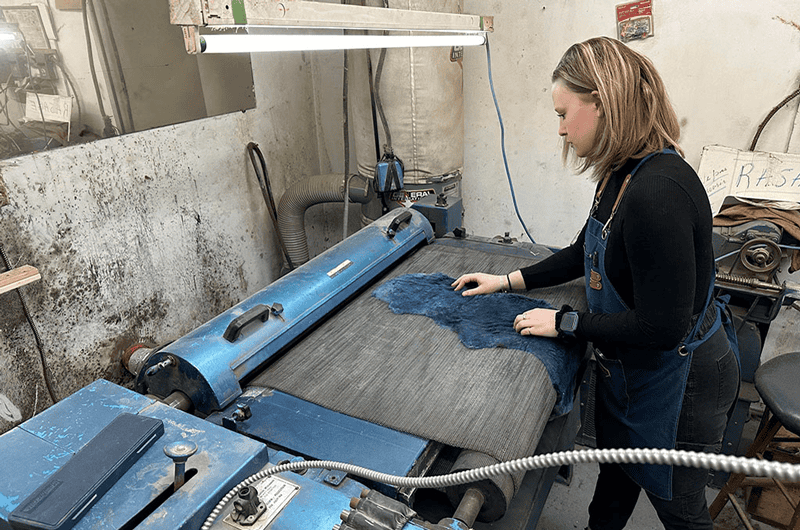

Processing

Shearing fur produces a soft, lush and velvety effect. Photo: Fourrures Gauthier.

Raw fur pelts are naturally beautiful, but they must go through certain processes to make them durable, supple and light enough for making into garments. In the following we’ll look at those processes that are considered essential, but there are many other optional processes now giving designers more flexibility than ever before to produce a remarkable range of special effects.

Most notable have been the development of ways to make fur pelts lighter and more supple, because that’s what consumers want. Indeed, fur pelts can now be made to resemble textiles, and can even be transformed into yarn and knitted!

DRESSING

The first step in preparing a pelt is skinning the animal. It is vital to keep the hide intact and avoid tearing it or causing any other damage. In a process known as “fleshing”, a special knife or revolving blade is used to remove as much flesh, fat and membrane as possible. The pelts are then dried.

The pelts then head to the dressing facility. To make it possible to work with the pelts, the leather is made supple by rehydrating it using chemical washes. There then follows a thorough cleaning to remove any dirt, blood, or contaminants from the leather and the fur. Mild soap and water can be used for this, while taking care to avoid stretching or damaging the fur.

All the washes cause the leather to thicken, so it is thinned down using a flesher’s knife. This is a skilled process. One false move and you’ll cut into the follicles and the hairs will fall out.

Then it’s time to preserve the leather to make it less susceptible to decomposing. There are different methods to achieve this, but most involve either tanning or salt-curing.

Tanning solutions use a variety of chemicals to preserve the leather. The main chemicals used are alum salts, including aluminum sulfate. These chemicals are more benign than those used to tan leather only, since the objective is different. When tanning leather only, the goal is to remove hair completely from the hide. With fur, however, it is essential to avoid damaging the hair follicles. Alum salts have been used for hundreds of years for water purification, to reduce the pH of garden soil, and for medicinal uses. Aluminum sulfate is the active ingredient in many anti-perspirants, and is used in styptic pencils to stop bleeding when shaving and to relieve pain from insect bites. Other commonly used natural ingredients are table salt (NaCl), water, soda ash, sawdust, cornstarch, and lanolin.

Gentle acids such as acetic acid (vinegar) are also used to activate the tanning process, but modern environmental protection controls ensure there are no harmful effluents. Excess fats are skimmed and pH levels must be neutralized before waste water is released from the tanning vats.

Animal rights groups like to sound the alarm on the use of formaldehyde in fur dressing, but their concern is misplaced, particularly these days. Formaldehyde is a naturally occurring chemical, being produced in all living things, plant and animal. It is also commonly used in industry. For example, the textile industry uses formaldehyde-based resins as finishers to make fabrics crease-resistant, and it forms the basis of adhesives used in plywood and carpets. It’s true that some people are sensitive to formaldehyde, particularly workers with long-term exposure by inhalation. This is why its use is being phased out. As for its use in fur dressing, it has not been used in North America for many years. It may still be used in Asian countries for dressing fur, but it’s definitely not required so the quantities would not be large.

As an alternative to tanning, the leather in fur pelts can be preserved by salt-curing. A generous amount of non-iodized salt is rubbed into the entire flesh side of the hide. It is then left to cure for several days, allowing the salt to draw out moisture and preserve the hide. After curing, excess salt is shaken off, and scraping removes any remaining flesh.

After tanning or salt-curing, the pelts are placed in a rotating drum of hardwood sawdust and mineral solution to clean and condition the leather. The pelts emerge still damp, so they are then dried completely. They are stretched taut over a frame or attached to a board, leather side up, then placed in a well-ventilated area away from direct sunlight. Drying may take several days or even weeks, depending on the thickness and size of the hide.

After the pelts are dried, they are then softened again to give them a more supple and luxurious feel. This can be done by rubbing a generous amount of vegetable oil or lanolin onto the leather, then tossing the pelts into a “kicker box” that causes the oil to penetrate the leather. The leather may also be kneaded, rolled or massaged to break down the fibres.

The pelts are then stretched using a spinning metal wheel, before entering the hot press, a process which irons and adds lustre to the fur.

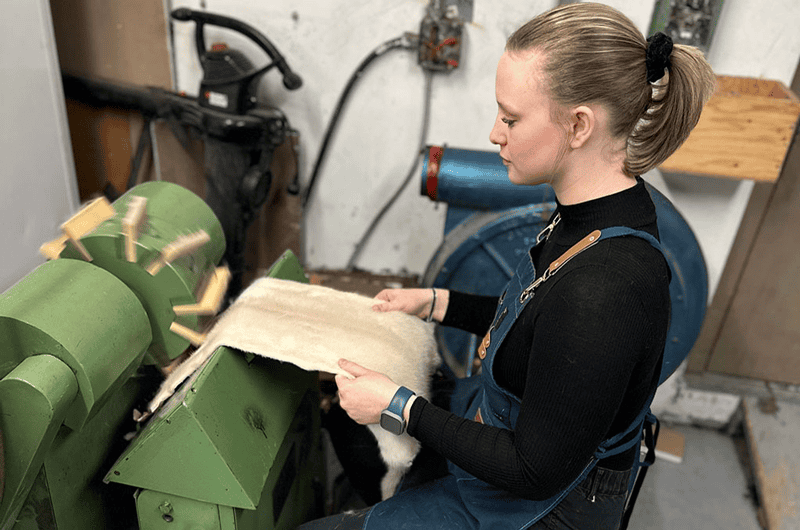

PLUCKING AND SHEARING

Traditionally, our fur pelts would now be ready to head to the garment factory, and many do just that. But increasingly these days, other processes come first, that further enhance the natural qualities of the furs. Three of these optional processes that are now commonplace are plucking, shearing and dyeing.

The majority of furs consist of two types of hair. Outermost are comparatively long, shiny, coarse hairs called guard hairs. These provide some protection for the animal against branches and other hazards, and a degree of water-proofing. Beneath the guard hairs is a layer of soft, dense underfur, which provides the most warmth.

Guard hairs are plucked to make a fur garment softer, lighter and less bulky without sacrificing much of the warmth. Photo: Fourrures Gauthier.

A few species have all guard hairs and no underfur, such as true seals, goats and antelopes. And a few species have all underfur and no guard hairs, such as chinchillas and rabbits.

In order to provide softer, lighter-weight and less bulky fur apparel without sacrificing much of the warmth, the guard hairs are sometimes removed, or “plucked”, by hand. The underlying “duvet” can then be sheared to a uniform pile, producing a soft, lush and velvety effect.

These two processes have long been used for beaver pelts, and North American processors are recognized for producing the finest plucked and sheared beaver apparel. However, plucking is a labour-intensive process that is increasingly being by-passed as processors go straight to shearing.

Shearing (with optional plucking) is also now widely used for other furs, including mink, muskrat, otter and raccoon.

DYEING

Traditionally, more expensive fur pelts tended not to be dyed because they came in such extraordinary natural colours. Rather, dyeing was mainly used for cheaper furs, in particular rabbit, in an attempt to look like more expensive pelts. In recent years, however, dyed furs have gained popularity among designers and consumers. Pink mink? Purple beaver? No problem!

However, like fur dressing, the dyeing of fur must be done gently so as not to harm the hair follicles.

OTHER PROCESSES

A range of new processing techniques now make it possible to produce furs that are lighter-weight and more supple than ever before.

Furs may now be married with leather or other materials. The skin side may be processed as leather or suede (“double face”) providing a reversible garment. In addition to plucking and shearing, fur may be grooved, sculpted (“laser cut”), printed or knitted. Intarsia techniques treat fur like a stained glass window or mosaic, producing what can best be described as “wearable art”.

We have come a long way from the traditional fur coat. Innovative dressing, dyeing and texturizing processes now inspire the designer and allow the creative process to begin even before the specific styling has been conceived.